Exploring the Role of the Gut Microbiome in Alzheimer’s Disease

- Qi An

- Jan 2

- 3 min read

Authored by: Qi An

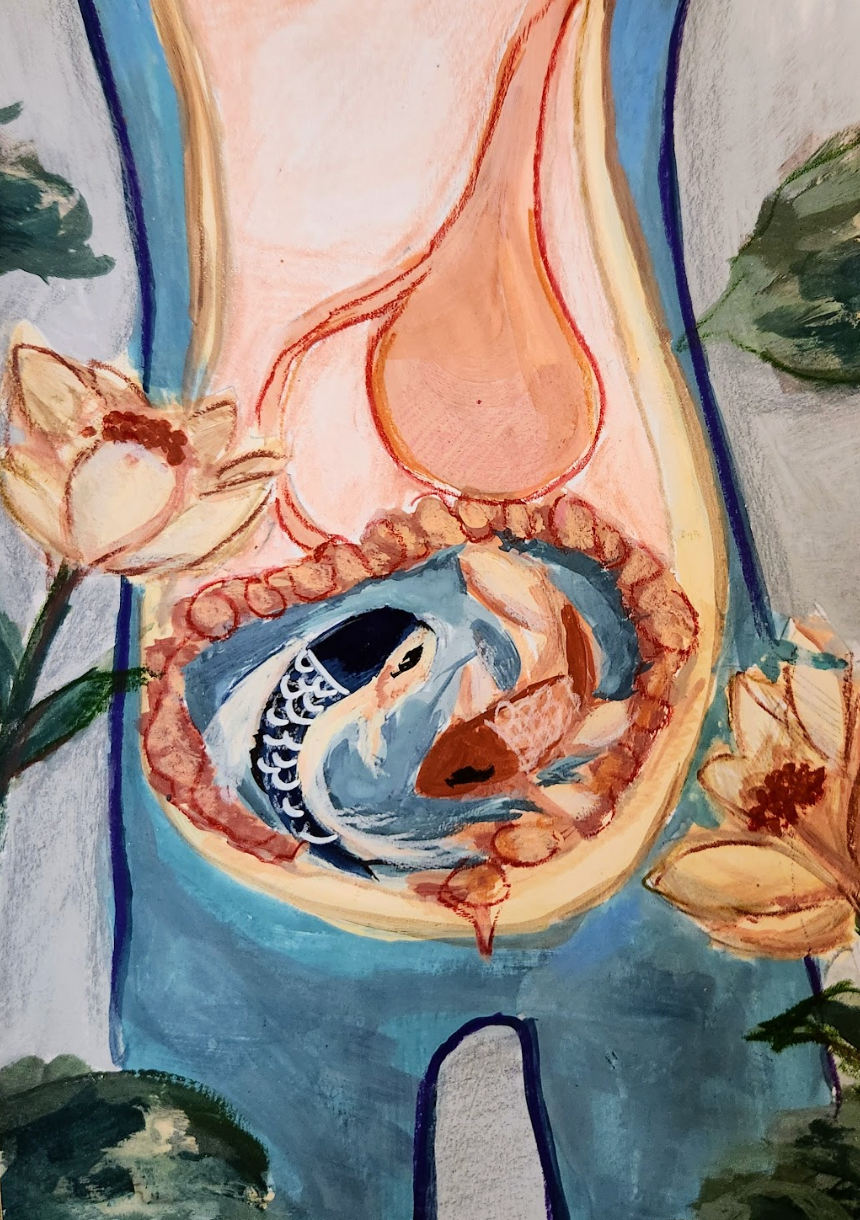

Art by: Vanessa Chen Hsieh

Prior research indicates that an estimated 6.9 million Americans age 65 and older are living with Alzheimer's dementia today. This number could grow to 13.8 million by 2060, approximately 14.7% of the total elderly population in the United States. [1] Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia in individuals over the age of 65. Unfortunately, There’s currently no cure for Alzheimer’s disease except medications that help relieve the symptoms. However, recent research on the role of microbiome play in brain function have shown great progression and potential treatment plans. [2]

The cause of Alzheimer's disease is related to multiple factors, including the genes, living conditions, and the environment. The gut microbiome plays an important role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease, other than the influences of genetics, lifestyle, and environmental factors. People often consider it unimportant due to the neglect of publicity. Changes in the gut microbiome can disrupt the balance of the central nervous system through the gut-brain axis, ultimately contributing to the pathology. Most microbiomes are beneficial to the human body. However, there is a small portion of them that are harmful such as microbial amyloid. It is a sticky protein made by some gut bacteria, which leads to amyloid buildup in the brain.[3] A deeper understanding of this relationship could guide the development of new therapies and raise public awareness.

A type of protein named curli produced from bacteria like E. coli is one example of an amyloid protein. Its shape is similar to the harmful amyloid found in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. Toll-like receptors in our gut lining will send out inflammation signals to alert the immune system when they detect curli or other harmful bacterial proteins. The receptors act as barriers and are responsible for protecting the body from harmful germs. Parts of the gut called Peyer’s patches will later receive these signals. Peyer’s patches are made up of clusters of immune cells. The inflammation spreads through the whole body and reaches the brain. It leads to the extra production of amyloids like beta-amyloid and alpha-synuclein because the brain is sensitive to inflammation and will be overactive to the signals. This cycle continues the harmful protein clumps form. Accumulated amyloids will misfold and form clumps or plaques that harm brain cells.It results in a chain reaction. One misfolded protein can cause others to misfold too and spread the damage. [4] . This is called “cross-seeding”— a bad protein triggers healthy human proteins to misfold. At the end-stage, dysfunctional brain will cause dehydration and infection, leading to death.[5]

The negative impact of microbiome emphasizes the importance of maintaining a high-fiber diet in daily life. High-fiber foods have been proven to reduce brain inflammation. Brain inflammation is considered the key factor in developing Alzheimer’s disease. Intake of high-fiber food facilitates the growth of healthy gut bacteria. These bacteria can break down dietary fiber into short-chain fatty acids, which have anti-inflammatory properties and can improve memory.[6] In conclusion, maintaining a healthy diet is an important key factor in preventing Alzheimer’s disease. How SCFAs regulate microglial activity in the aging brain remains an unsolved question. Scientists are conducting further investigations.

References:

2024 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. (2024). Alzheimer S & Dementia, 20(5), 3708–3821. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13809

Li, J., Mou, H., & Yao, R. (2025). Gut-Brain Axis and a Systematic approach to Alzheimer’s disease therapies. Brain Science Advances, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.26599/bsa.2024.9050031

Liang, Y., Liu, C., Cheng, M., Geng, L., Li, J., Du, W., Song, M., Chen, N., Yeleen, T. a. N., Song, L., Wang, X., Han, Y., & Sheng, C. (2024). The link between gut microbiome and Alzheimer’s disease: From the perspective of new revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer S & Dementia, 20(8), 5771–5788. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.14057

Beyond the brain: the gut microbiome and Alzheimer’s disease. (2023, June 12). National Institute on Aging. Retrieved November 3, 2025, from https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/beyond-brain-gut-microbiome-and-alzheimers-disease#looking

Seo, D., & Holtzman, D. M. (2024). Current understanding of the Alzheimer’s disease-associated microbiome and therapeutic strategies. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 56(1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-023-01146-2

Williams, Z. a. P., Lang, L., Nicolas, S., Clarke, G., Cryan, J., Vauzour, D., & Nolan, Y. M. (2024). Do microbes play a role in Alzheimer’s disease? Microbial Biotechnology, 17(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.14462

Comments